Health issues are not limited to the body we live in. A wide range of factors removed from our physical self can impact our health—adequate housing, food security, income levels and education are just a few of the social determinants affecting health outcomes. The nature of these issues are complex; many can not be dealt with by the health sector alone. An intersectoral approach—involving those working in the education, social and justice sectors, as well as community members—is needed to not only examine these issues from multiple perspectives, but to work towards a solution: optimal health for all.

Table of contents

Health: More than just physical

The status of one’s health has just as much to do with their social world as their physical world. This is according to Michael Marmot, a physician and advisor to the World Health Organization (WHO), who served as chair of its Commission on Social Determinants of Health. The commission’s final report, released in 2008, addressed myriad factors influencing health inequities around the world. These social determinants of health include:

- Income and social protection

- Education

- Unemployment and job insecurity

- Working life conditions

- Food insecurity

- Housing, basic amenities and the environment

- Early childhood development

- Social inclusion and non-discrimination

- Structural conflict

- Access to affordable health services of decent quality.

This leads to persistent and widening gaps between those with the best and worst health and well-being, as poorer populations systemically experience worse health than richer populations. For example, data from the WHO shows:

- There is a difference of 18 years of life expectancy between high- and low-income countries.

- In 2016, the majority of the 15 million premature deaths due to non-communicable diseases occurred in low- and middle-income countries.

- Relative gaps within countries between poorer and richer subgroups for diseases like cancer have increased in all regions across the world.

- The under-five mortality rate is more than eight times higher in Africa than the European region.

The WHO concludes that reducing social inequalities in health and thus meeting human needs is an issue of social justice.

This is to say, our health and well-being is about more than the curative practices performed within the health system. For example, there is substantial research showing that access to early childhood education and development can influence whether someone completes high school, attends post-secondary, even what their long-term financial situation could look like. Similarly, nutrition in the first two years of life has a critical effect on the developmental outcomes of a person’s life over the long-term. These social determinants are profound. As such, it’s important to consider the broader health of populations, particularly in the context of equity, as we start to segment our population into groups that have access to services, and those with less access (or perhaps no access) in some parts of the world.

Intersectoral case studies

Brandon Bennett is a quality improvement (QI) expert and principal advisor of Improvement Science Consulting, based in San Francisco. Bennett works with clients in health care and education to improve their processes and boost quality outcomes. These projects are often intricate, with many stakeholders spanning multiple sectors, tackling complex issues.

Working with populations in a cross-sectoral manner involves bringing together different human services sectors including health care, education, judicial and social welfare systems—recognizing they may each contribute to the social factors that influence an individual’s health. Ultimately these intersectoral relationships can lead to upstream improvements in health and well-being. He detailed three cases of note for us at a past QI Power Hour.

Helping Families Initiative

The Helping Families Initiative was established in 2003 in Mobile County, Alabama by then-district attorney John Tyson. Historically, Alabama experienced high rates of poverty and low rates of both high school graduation and literacy. During his tenure, Tyson noticed a pattern: he was repeatedly prosecuting young Black men who, after their conviction, had a difficult time re-entering society—they couldn’t vote or find gainful employment, and the tendency to reoffend was high. Tyson looked back to the school system as a point of intervention to potentially prevent crime in the community before it happened.

He re-visited a law first passed in the state legislature in 1927, which called for district attorney intervention if a child is chronically absent from school or is suspended from class for a serious offence. The district attorney’s office then contracts a social worker to reach out to that child’s family. It is not mandated by the state; family participation is completely optional. But if they do participate, the social worker acts as a care coordinator to identify any areas of concern—whether it be housing, food security, job placement or education services—and connect them with the appropriate organization. The family is reassessed every three months and progress is measured using the North Carolina Family Assessment Scale, which is used by social agencies to measure family functioning. Additionally, the district attorney’s office has access to data dating back to 1927 identifying which families may be experiencing systemic hardships as a result of child absences.

The program results were profound. In the Montgomery County School System, 80 per cent of students with initial suspensions never faced suspension again. Unexcused absences dropped by 24 per cent, and school suspensions overall dropped by 30 per cent—an important statistic as they occurred more in children of colour than white children. It is an excellent example of intersectoral collaboration; by working with stakeholders in the education system, the district attorney was able to intervene and create meaningful change impacting the justice system.

Kia Kaha

Brandon’s next case was an ocean away at a primary health institution in Auckland, New Zealand. The team at Tamaki Health saw a high number of repeat patients presenting in the emergency rooms with chronic health conditions that were placing a heavy burden on the health system. The goal was to reduce unplanned emergency presentations by 25 per cent in participating patients.

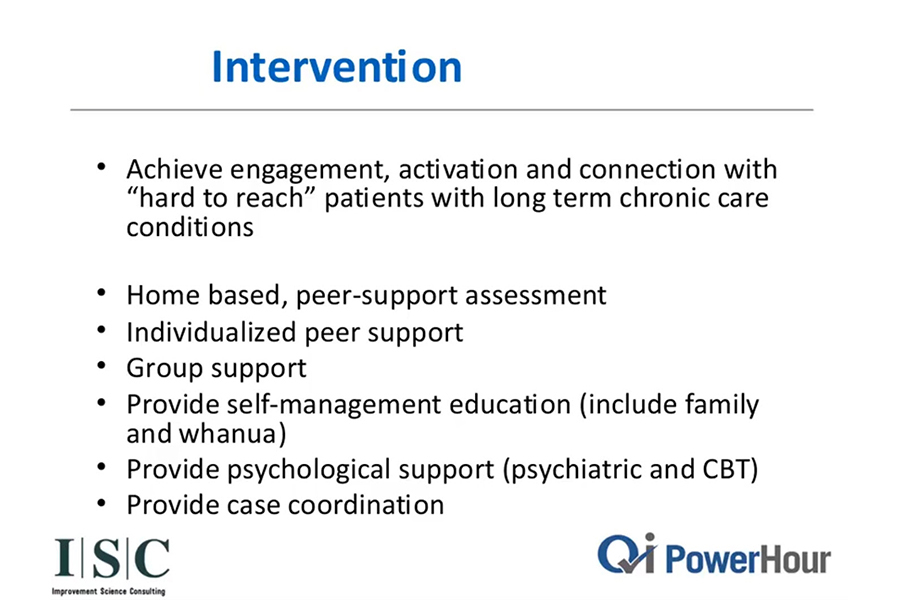

So the team worked with Counties Manukau District Health to establish Kia Kaha—a phrase used by New Zealand’s Indigenous Māori people, meaning stronger together—in 2013. The intervention had three pillars: engagement, activation and connection.

A crucial part of the program was the establishment of peer support groups, members of which provided in-home visits to chronically ill patients in the community. These hard-to-reach patients—called such because they tend to miss appointments and typically lack adherence to medication protocols—are, from a caregiver’s perspective, challenging to work with. However, the system, as it is set up, is not working for them, and health-care leaders sought to meet these patients where they were at.

As it turned out, many of these patients with long-term chronic illnesses were withdrawn and depressed. They reported feeling isolated and lonely as a result of their health issues. The peer support workers were able to assess these patients and determine if further intervention (such as counselling or referral to another agency) was needed. Support workers also provided self-management education to families, called whānau (another Māori term meaning community and family together). The program was even adapted into multiple languages to support Indigenous and immigrant groups in Auckland.

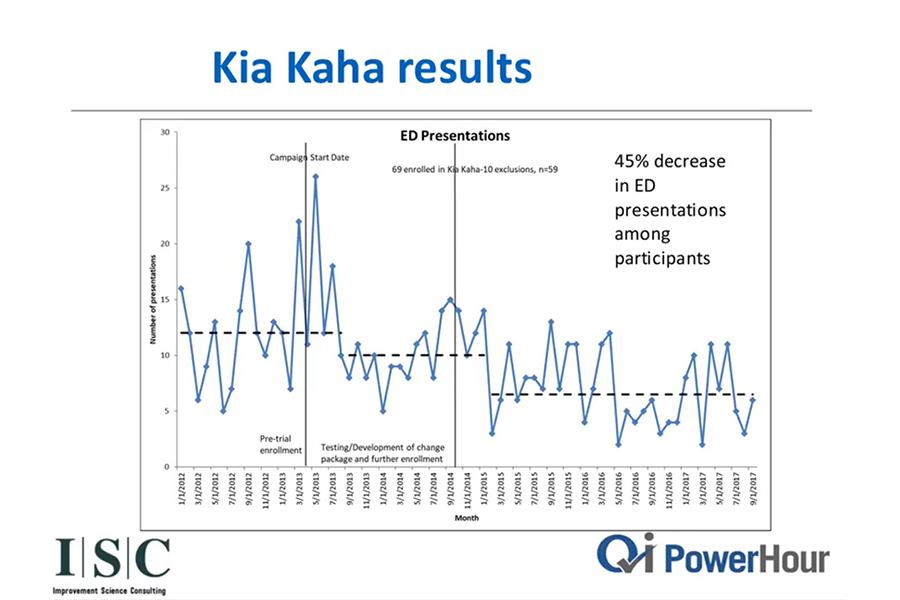

In the first year of Kia Kaha, there was a 41 per cent drop in emergency room presentations amongst the patient cohort—far surpassing the initial goal of 25 per cent. Additionally, engagement with the cohort—previously labeled as hard-to-reach—nearly doubled, speaking to the program’s commitment to patient connection. These participants reported a massive improvement in their quality of life. At program learning sessions, they spoke of a stronger connection to their families and communities. This intersectoral intervention—between health care and the community—relieved pressure from an overwhelmed emergency room, provided cost savings to a public health system and brought tangible positive outcomes to patients previously not engaged in their health care.

Cincinnati Child Poverty Collaborative

The third case study looked at a poverty initiative in Cincinnati, a mid-size American city. With a manufacturing sector that’s been on the decline since the eighties and nineties, the area has been hit with high unemployment and economic depression. Cincinnati’s child poverty rate is also among the highest in the country.

One recent program, the Child Poverty Collaborative, has been effective in health-care quality improvement and looking upstream to address the social determinants of health. Launched in 2015, its aim was to tackle the high rate of child poverty in the community. The project had big ambitions: lift 10,000 children representing 5,000 families out of poverty within a five-year timeframe. There were many stakeholders involved, including the mayor’s office, a children’s hospital, faith groups, health organizations, the business community and local not-for-profits.

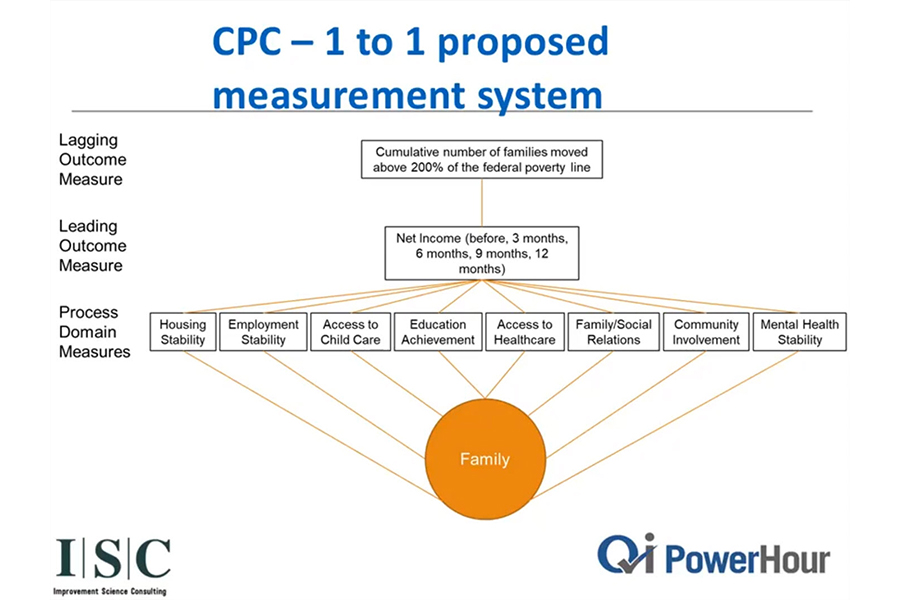

A tricky component of an endeavour like this is measurement—how do you measure poverty? In this case, net income has become an important point for understanding these levels. Each time a new family connects with a partner agency and enrolls in an intervention pathway—be it new housing, job placement or enhanced food security—they complete an income verification sheet. They provide this information again, three months and six months later. The data is then aggregated throughout the city and the collaborative can understand at further timepoints if the community involvement is effective.

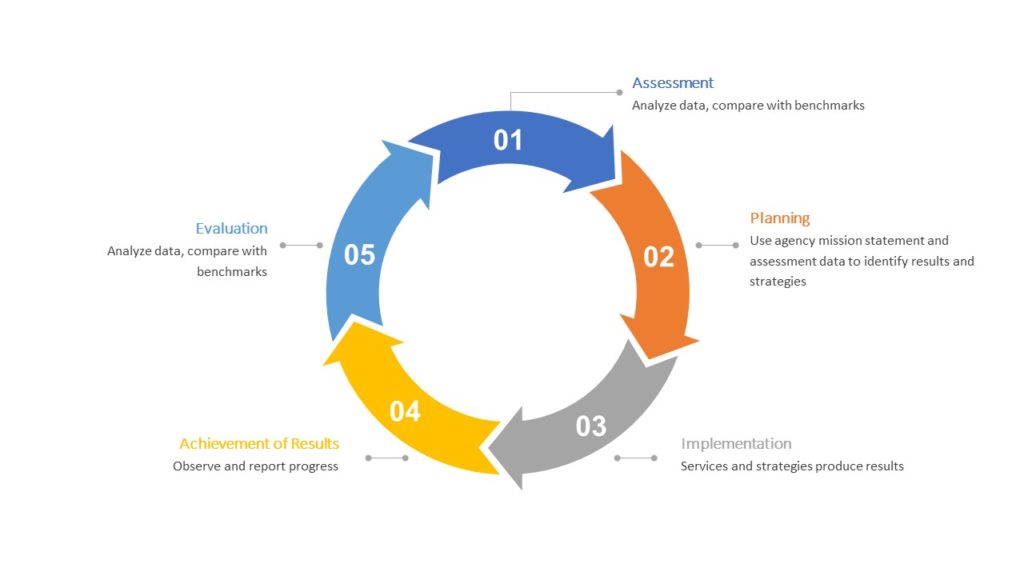

Another useful measurement tool used in this process is the Results Oriented Management and Accountability (ROMA) framework, which provides a framework for continuous growth and improvement in community services. It looks at family stability through process measures or process metrics—if we can move the needle on an issue like housing or employment, the more likely we can move in the same direction on people’s health outcomes.

In this case, ROMA’s focus is more on predicting family stability, with the assumption that the more stable a family, the better the health outcomes.

Conclusion

The social determinants of health construct acknowledges the complex and systemic realities that influence health outcomes. These issues are complicated and multifaceted; a health issue may also be linked to issues of income, housing, education levels, or access to food. As such, there is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all solution. However, stakeholders can ultimately cover more ground by building relationships across relevant sectors and uniting with like-minded groups sharing a common goal of optimal health for all.

Related content

- Thinking Upstream: Intersectoral Quality Improvement for Better Health and Wellness (QI Power Hour)

- HQC Community QI Collective