Table of Contents:

- Diving deeper into health and what impacts it

- Why should we shift to an upstream thinking approach?

- Health Inequalities vs Health Inequities

- Evidence for an upstream approach

- What can I do about the determinants of health in Saskatchewan?

Whether you are new to the world of the determinants of health or looking for a refresher, here’s a primer on this topic.

If we asked you to think about the things that make you healthy, what comes to mind?

Health is more than just access to health care services

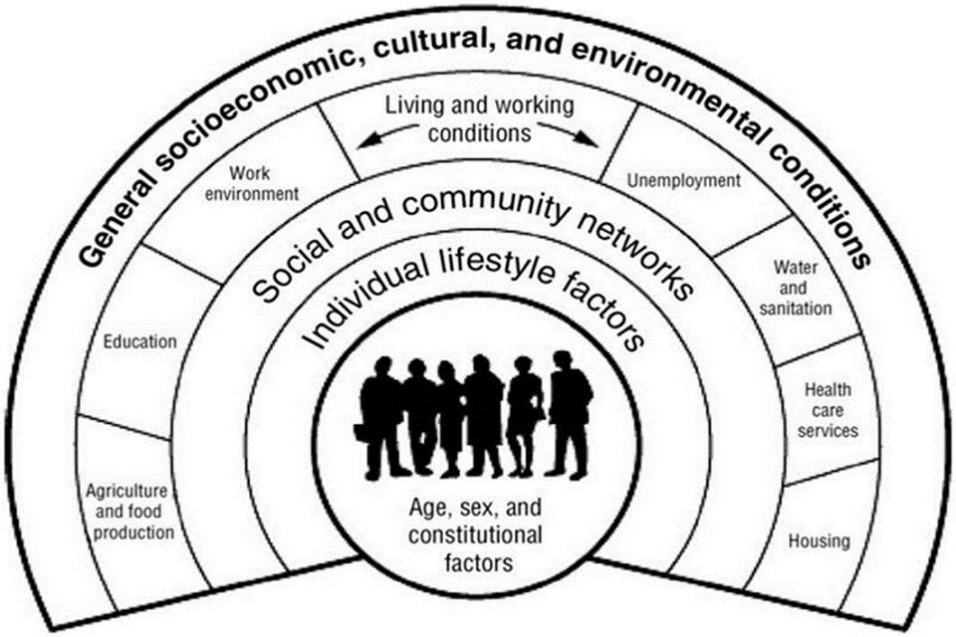

When Canadians think about health, we often think about healthcare and individual behaviours like diet and smoking. But what makes us healthy or not goes far beyond access to health care services. In fact, studies suggest that up to 75% of the things that make us healthy are not part of the healthcare system. Instead, the greater contributors of health are found in the conditions in which we are born, grow, live, work, and age. They include things like your education, job, relationships, and where you live. They are collectively referred to as the social determinants of health. The social determinants of health encompass the personal, societal and environmental conditions that can either support or hinder health.

While there have been dedicated efforts to address these factors for many years, you can’t miss the presence that these topics have held in many media outlets in recent years, with a renewed focus on what many have long known to be true.

Diving deeper into health and what impacts it

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes health as not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, but rather “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being. This means that supporting the health of a population includes ensuring health systems can treat the illnesses and conditions that people face at various points in their lives, but also supporting people beyond their interactions with health systems so that they may lead healthy, happy, and productive lives in their communities.

The social determinants of health, as defined by the WHO are “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age” and play an important role in our population’s overall wellbeing.

In Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada recognizes the following key determinants of health:

- Income and social status

- Employment and working conditions

- Education and literacy

- Childhood experiences

- Physical environments

- Social supports and coping skills

- Healthy behaviours

- Access to health services

- Biology and genetic endowment

- Gender

- Culture

- Race / Racism

There is also growing literature outlining that there is great variety in the determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health. In the 2015 book Determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ Health in Canada: Beyond the Social, the authors recognize colonialism as the broadest and most fundamental determinant of health for these populations. The authors argue that, in addition to the structural aspects of society that drive patterns of health, there are many other factors that have significant impact on Indigenous peoples’ health, including spirituality, relationship with the land, language, culture, history, and self-determination.

The National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health suggest that inequalities in the social determinants of health can further act as barriers to addressing health disparities experienced by this population. They illustrate the interconnectedness and often compounding effects of the social determinants of health in the following example: “Living in conditions of low income have been linked to increased illness and disability, which in turn represents a social determinant, which is linked to diminished opportunities to engage in gainful employment, thereby aggravating poverty.”

Simon’s Story

Consider the story of Simon, below, from the 2001 Commission on Medicare publication Caring for Medicare: Sustaining a Quality System, that illustrates the complex interaction of these factors that influence the lives of individuals and families:

Simon is in the fifth grade in the year 2010 and finds school to be quite a struggle. He manages to just scrape by. Simon lives with his mom – his parents split up when Simon was three. She does her best to pay the bills. Four different childcare workers looked after Simon before he started school; his mom was relieved when he began going full-time in grade one.

Simon spends most of his time watching television and hanging out at the mall with his friends. His school used to have an after class recreation program, but that was dropped in the latest round of budget cuts. He also used to get extra help with his homework, but now that’s gone too. Simon has asthma and his mom finds it difficult to cope. As a result, he spends a lot of time in hospital emergency waiting rooms.

By 2016, after being held back in school twice, Simon is a 16-year-old ninth-grader, but his marks are poor. He spends less and less time at school and decides that it’s not really what he should be doing with his life anyway. He leaves school partway through the year and tries to keep up with the demands of the part-time jobs he has taken. Unfortunately, he has messed up the balance on the cash register too many times and his boss, the kindly Mr. Green, has to let him go.

Simon gravitates to the seamier side of his neighbourhood, and his mother wishes they could move, but they’re trapped. He spends many nights getting drunk and taking drugs. By 2020, he has been in and out of jail several times for dealing drugs. When he’s not in jail, he’s often in hospital for his asthma, complicated by hepatitis C. Simon will be lucky to see 2050, and society will spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to incarcerate him and treat his illnesses.

Simon’s story illustrates the complex interplay of factors that influence his decisions, and ultimately impact his overall health and well being. It is difficult to determine one root cause for the situations Simon finds himself in, later in life. Rather, the family would have benefited from multiple supports at various points, to possibly change the trajectory of both of their lives.

Why should we shift to an upstream thinking approach?

There is an important role for health services in maintaining overall health. Those working in health care have incredibly important roles to fill for patients requiring services to treat and manage illness, disease and trauma. But there has been increasing reliance on emergency departments and hospitals in recent years. The solution has often been to continue investing time and energy into acute care, instead of focusing on what is driving individuals to the hospital’s doorstep.

The parable of the river is often used to illustrate the concept of upstream and downstream thinking. Imagine you are standing next to a river, and see people floating down the river calling for help. Your response is to dive in and save them. But the people just keep coming down the river, and eventually, you become exhausted and feel overwhelmed. Then someone asks, “Why are these people ending up in this river, anyway?”, and travels upstream to find out.

How do we work towards an upstream approach?

Thinking upstream means understanding and addressing the root causes of medical issues and redesigning systems, where possible, to prevent people from falling into the river in the first place. An approach could involve examining how factors like a lack of housing, food insecurity, or social isolation are contributing to illness and disease. In the words of Sir Michael Marmot, the Chair of WHO’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, “why treat people and send them back to the conditions that made them sick?”. Upstream thinking takes this idea to heart and looks at the conditions that lead people to require health services in the first place – identifying the “causes of the causes”.

Health Inequalities vs. Health Inequities

When we talk about the social determinants of health, the topic of health equity often comes up. But what exactly is health equity?

Health equity

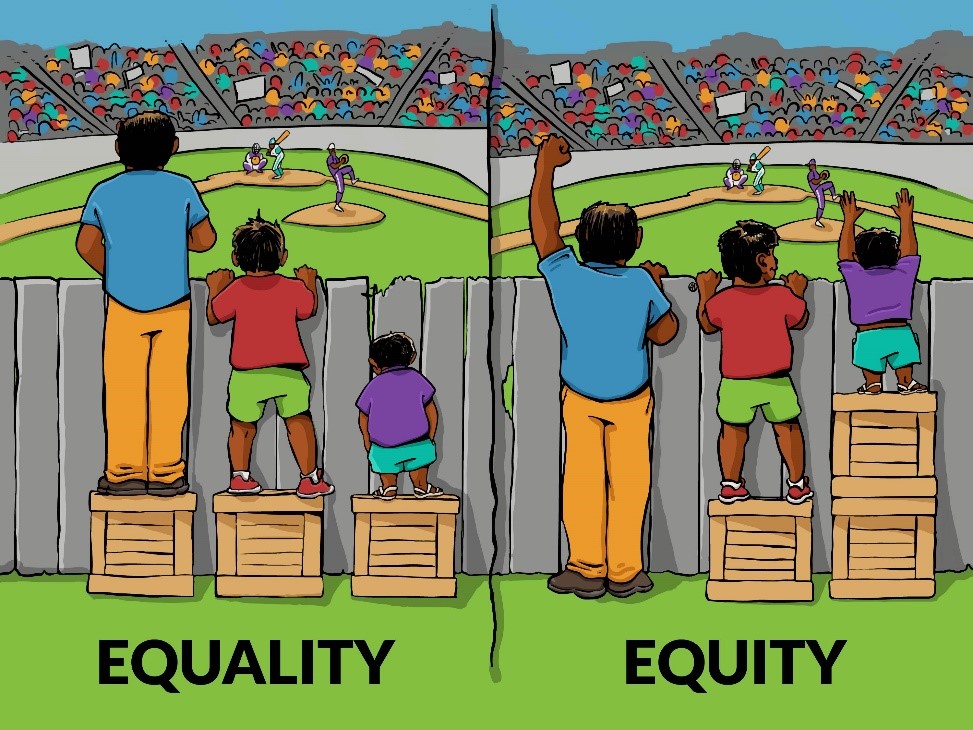

Health equity is the idea that individuals should have a fair opportunity for a healthy life, regardless of their social or environmental circumstances. It is important to distinguish equity from equality. As illustrated in the image below, equality means that all people get the same thing. Equity means everyone gets what they need to lead a healthy life, meaning those with worse health and fewer resources may require more efforts to improve their health.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation offers the following definition of health equity: “Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. This requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and health care.”

Health inequalities

Health inequalities refer to the differences in health status experienced by different groups or populations. Examples of health inequalities could range from differences in mobility between elderly people and younger populations, or differences in mortality rates between people from different socio-economic statuses. Some health inequalities can be caused by biological factors and individual choice, while others are caused by conditions largely outside an individual’s control. When health inequalities arise from conditions that are avoidable and unfair, they are considered health inequities. In many cases, health inequitiesare influenced by the social determinants of health as well as larger structural barriers that persist in our society, such as poverty and discrimination.

Health inequities and incomes

As an example, many studies have shown that those with higher incomes are often healthier than those with lower incomes. In Saskatchewan, the 2006 study “Health Disparity by Neighbourhood Income” published in the Canadian Journal of Public Health found that the 6 lowest income neighbourhoods in Saskatoon had significant health inequities when compared to higher-income neighbourhoods. When the poorest 6 communities were compared to the wealthiest 6 communities in the city, the residents from the lower-income communities were:

- 15 times more likely to contract a STI

- 15 times more likely to attempt suicide

- 35 times more likely to have type 2 diabetes

Mortality rates were 2.5 times higher for adults and 3 times higher for infants living in the lowest income neighbourhoods when compared to individuals living in the highest income neighbourhoods.

Health Equity recommended resources:

- Let’s talk Health Equity – National Collaborating Center for Determinants of Health

- Health Equity – World Health Organization

Evidence for an upstream approach

Across the globe, good health is a shared goal of both individuals and societies. And yet many of us take our good health for granted, not realizing that it is one of the key enablers to pursue other goals and priorities in our life. When it is threatened by illness or disease, our pursuit to regain health becomes our primary focus and priority. Once our health is in jeopardy, many of us reflect on the fact that good health is the cornerstone of the rest of our life. It influences the job we hold, our relationships with others, and how we spend our free time.

Making the case for investment in the social determinants of health

Many community-based organizations, non-profit organizations and charities are rooted in the moral case for the investment in the social determinants of health. Many join this effort because they feel it’s the right thing to do, and are motivated by the idea of a fair and just society and a commitment to taking care of the members of our communities.

In addition to this perspective, there is also growing evidence of the economic benefits of investing in the social determinants of health. For example, a 2017 research report by the Rand Corporation found that a Permanent Supportive Housing program, launched by the Department of Health Services in Los Angeles County reduced participants’ use of public services (including health services, social services, and law enforcement services) by close to 60% per year, after receiving stable housing through the program.

The yearly cost savings of the program more than covered the yearly cost of the supportive housing program and resulted in a net cost savings of 20% to the country. In September of this year, Toronto’s University Health Network Hospitals announced plans to dedicate a plot of hospital-owned property to build an affordable housing project, to help ease overcrowding at the network’s two hospitals, recognizing the linkage between housing and health.

In other words, there’s growing recognition that investing in the social determinants of health is not just the right thing to do, it’s also good business. In healthcare, debates about the future sustainability of our publicly funded system are ever-present, due to growing cost pressures with an increased population and burden of disease. There is strong evidence that upstream investments in the social determinants results in downstream savings to multiple sectors including health care, social services and policing and corrections. Healthy individuals are also more likely to be productive, engaged in work, and contribute to the economic well-being of their communities.

The Health Quality Council is expanding our role

The Health Quality Council is excited to be expanding our role to begin working upstream to support better health and wellness. We are eager to be adding our voice to those who have spent many years building the evidence base for this approach. The Health Quality Council was born out of the Fyke Commission’s 2001 report Caring for Medicare: Sustaining a Quality System, with a mandate to improve the quality of health services in the province. We plan to continue contributing to this end, as we have over the past 17 years, supporting changes that will help achieve an alternate framing of Simon’s story, as envisioned by Kenneth Fyke in 2001.

Simon’s Story (continued)

Simon lives with his mom, Ruth. His parents split up when Simon was three and his mom struggled to make ends meet. Working at a minimum wage job, living in poor quality housing, dealing with Simon’s asthma, and struggling to find suitable childcare were taking a toll on her health.

At a periodic visit to the Primary Health Centre, Ruth broke down and disclosed her situation to the nurse. Seeing the complexities of the situation, the primary care nurse told her about an asthma management program for Simon. She also referred her to the social worker at her health centre who talked to Ruth about the almost completed new low-income housing project. The project will have a daycare, with a preschool based on a Head Start program. He also told her about the plans for an adult upgrading program to be held evenings at the health centre. Ruth could finish high school without having to worry about childcare for Simon.

The provincial budget brought more good news: a new child income benefit and plans for more investment in training and education programs for single parents. The social worker invited Ruth to a single parent support group for their area. The group talked about a wide variety of things like parenting alone, first aid, loneliness, and how to do your taxes. They also had a community kitchen and were organizing a Good Food Box co-operative.

Ruth left the appointment with renewed hope. She knew there were no free rides and it would be a long haul as a single parent. Somehow, she felt the playing field had been evened a little, and she and her son might have a fighting chance.

In this version of Simon’s story, health care serves not only in the role of providing health services but also as a linkage to other services to help improve other drivers of health. It speaks to the importance of a community-based approach to supporting individuals and families, of having an awareness of supports that exist from other sectors, and how to access them.

What can I do about the determinants of health in Saskatchewan?

Given all this, how can we work together in new ways to improve the health of our communities in Saskatchewan? One way to contribute to this end goal is to become better aware of what’s happening in our province and our country to work upstream and address the social determinants of health. We invite you to follow our blog series over the coming months, to learn more about the social determinants of health here in Saskatchewan.